Golden Sunset Moderna Museet Stockholm 2017

Found Space

Pigment print 125x153 cm

Inside out

Pigment print 53x63cm

Back and Front

Pigment print 63x53 cm

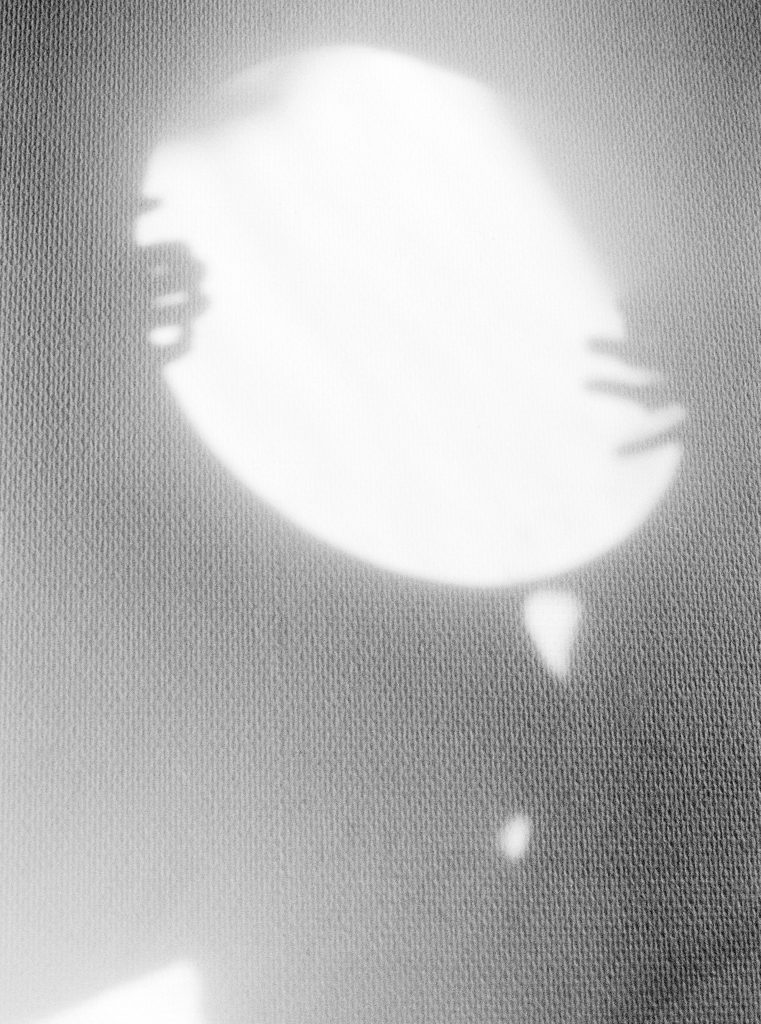

Air Ball

Pigment print 120x98 cm

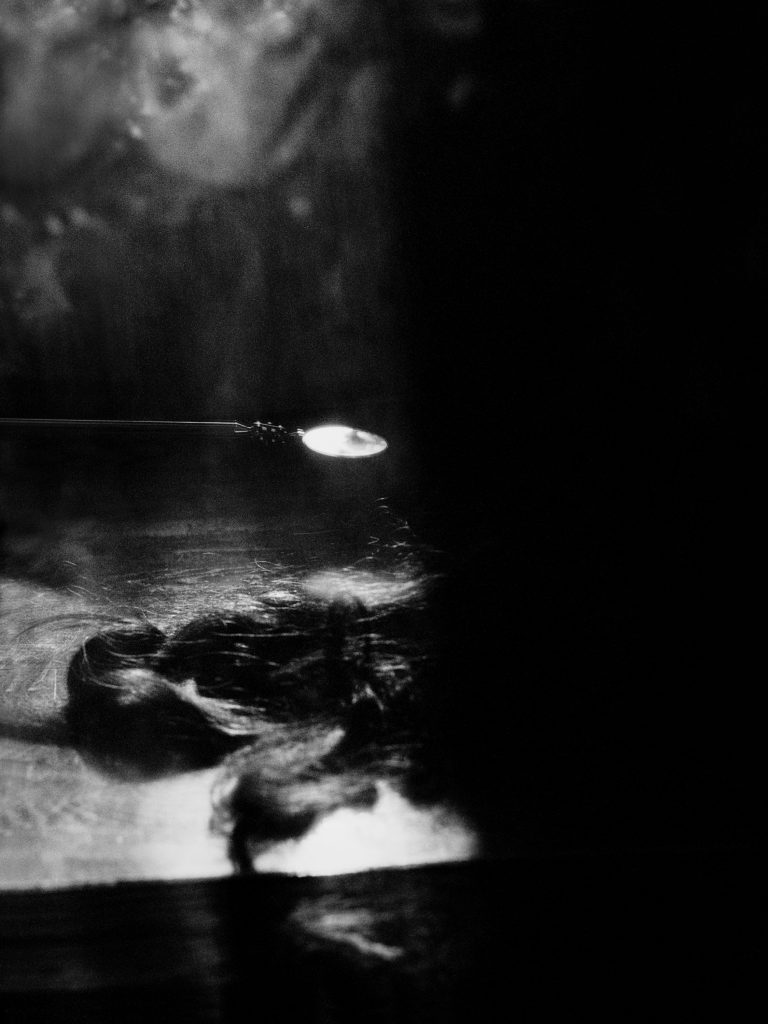

Hairs

Pigment print 63x53 cm

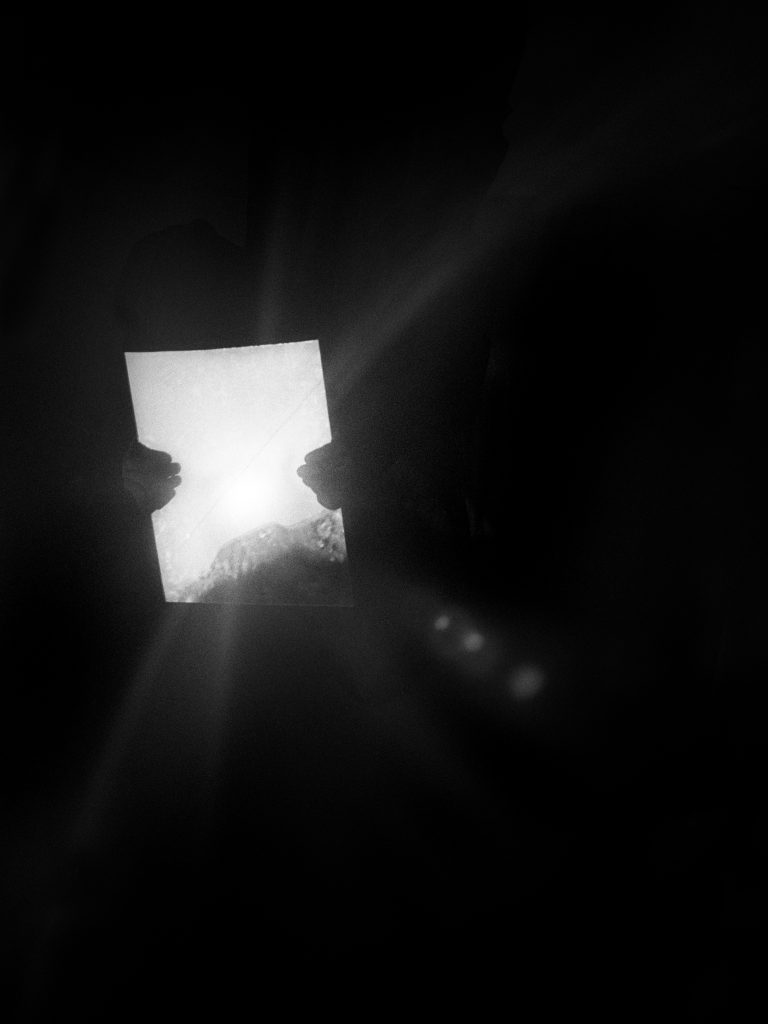

The Decision

Pigment print 120x98 cm

Signal vision

Pigment print 120x98 cm

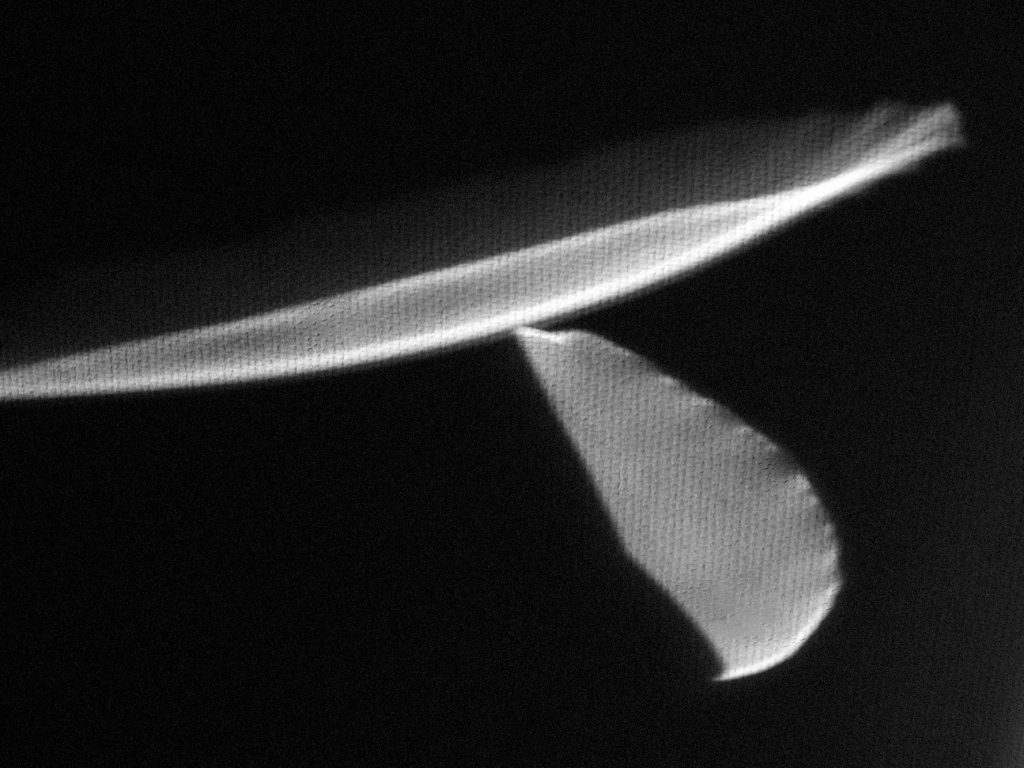

Inspection I

Pigment print 63x53 cm

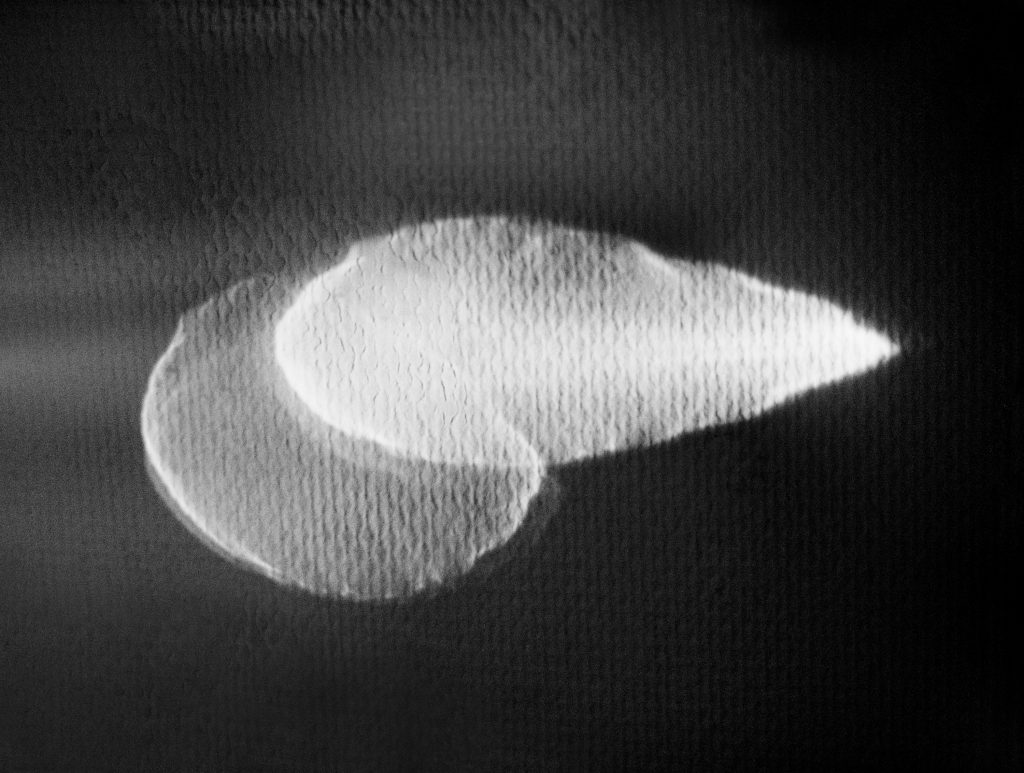

Inspection II

Pigment print 63x53 cm

Inspection III

Pigment print 63x53 cm

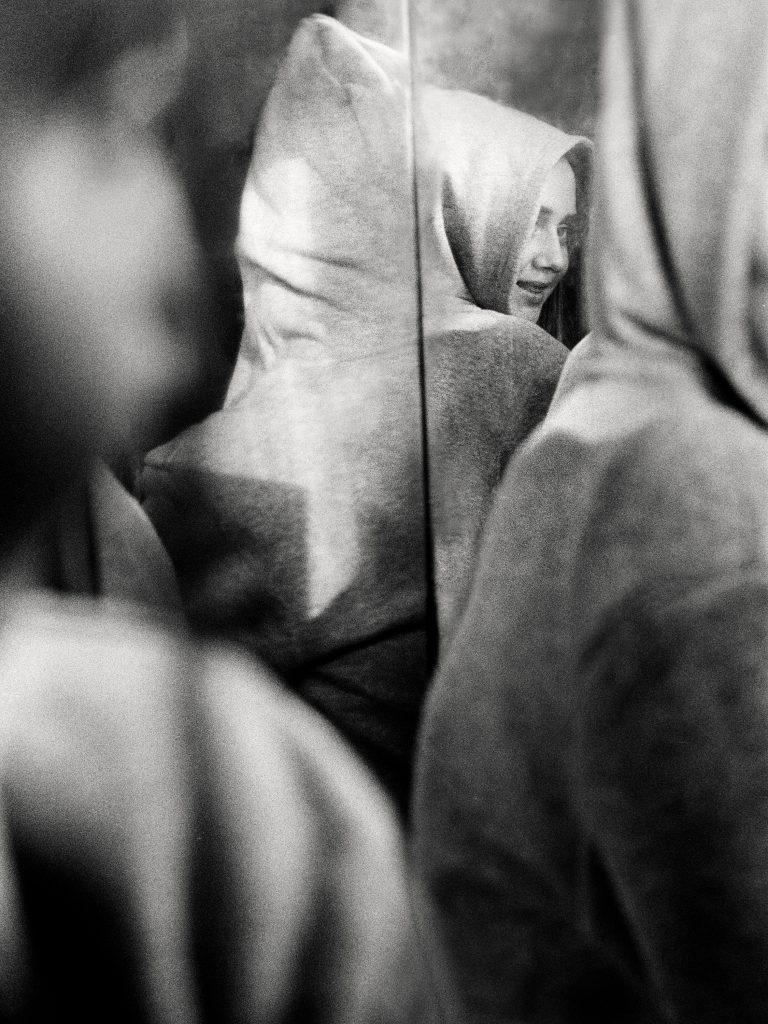

Hole in Curtain

Pigment print 63x53 cm

Up in the tree

Pigment print 63x53 cm

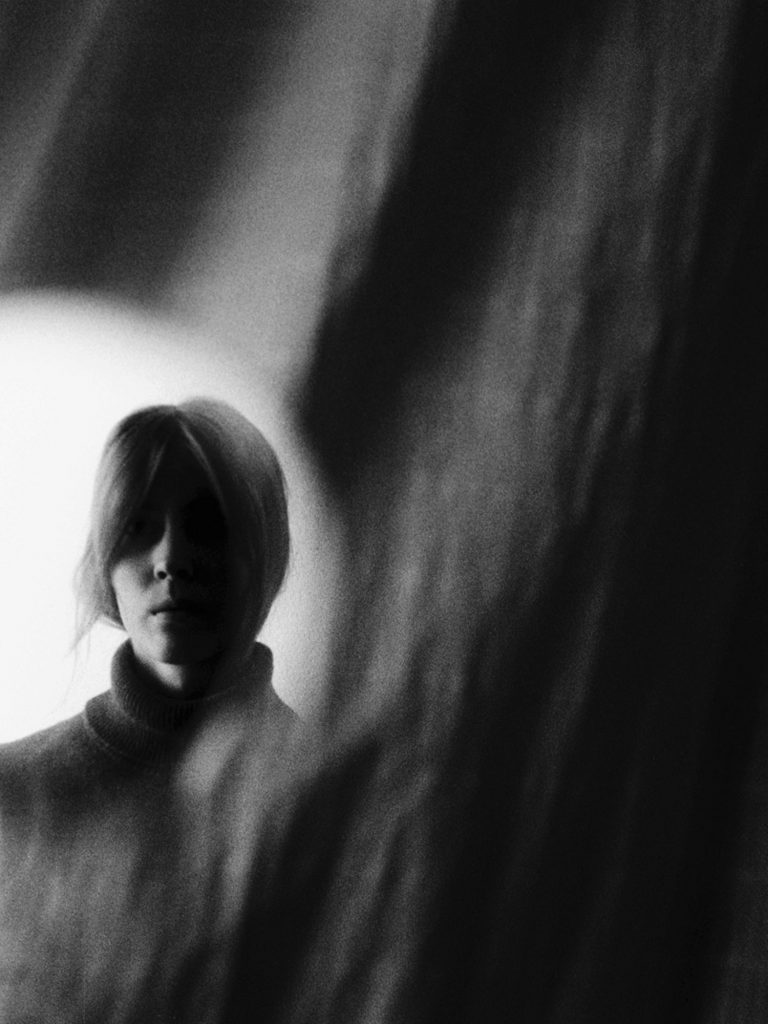

Two Heads

Pigment print 63x53 cm

Past Time II

Pigment print 98x120 cm

Two Bodies

Pigment print 60x50 cm

Window Cleaner

Pigment print 120x98 cm

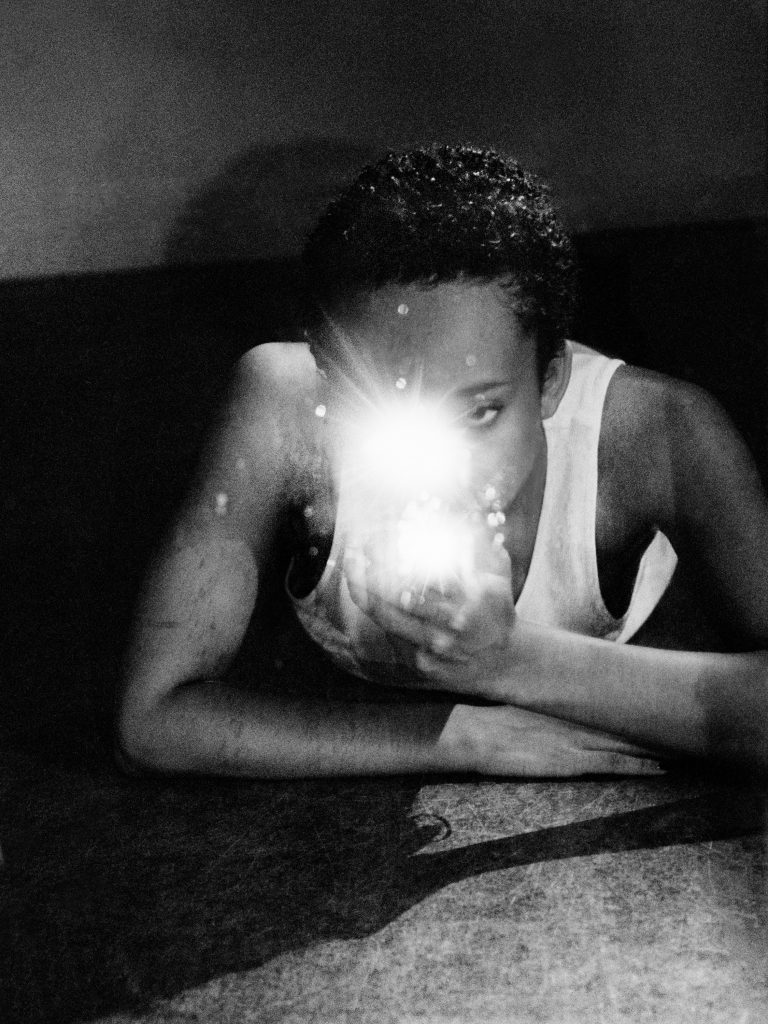

Light´s Up

Pigment print 120x98 cm

Past Time

Pigment print 98x120 cm

Upside down

Pigment print 53x63cm

Gap

Pigment print 98x120 cm

Earsmoke

Pigment print 53x63 cm

Hands on the Floor

Pigment print 98x120 cm

Inspection V

Pigment print 53x63 cm

Jenny Källman – Lounge

text by Nina Øverli

“Traditionally and historically photography has conveyed some kind of truth, though what’s not always discussed is the feeling of the actual – the struggles going on outside of the frame, before and after each shot.”

“We’re all victims and perpetrators in life.”

Jenny Källman (in conversation with Jeff Rian, Surveillance, 2012)

In her new body of work, Jenny Källman investigates a type of space and a world that remains closed to most of us; the prison cell. Working not only with still photography, but also with sound, music, and the moving image, she opens these spaces up to a mode of representation other than the strictly documentary. Several of these works have been made inside a prison for young offenders. But where a traditional documentary approach would simply reveal these spaces to us in all their starkness, Källman makes use of a form of abstraction that has a stronger capacity to describe the complexities inherent in the condition of confinement. Here, the use of geometric shapes, mirrors, darkness, and reflections, causes individual features to become indistinct, and creates a series of tensions between the generic and the particular that are both intensely appealing and strangely frightening. Through her deliberate use of abstraction, Källman manages to convey a sense of entrapment, of loops of thought caught up in a circular movement of repetition, and of endless games constructed to challenge and undo these traps.

The title of the series, Lounge, is an ironic take on the open-ended time and the shared social spaces of the prison as an institution. Here, the words “lounge” and “lounging,” stand in direct opposition to their usual connotations of comfort and leisure. One of these works was made based on conversations and visits with one particular young boy in prison, carried out during the year leading up to the works first being shown. The film that came out of these meetings shows part of his figure, obscured by the darkness and the camera angle. The boy’s personality is present in his voice, as he hums a tune and sings, his voice resonating through the yellow-tinged darkness of the prison cell. Made in close collaboration with the young boy, this is his own song that he is singing, and these are his own choices that have been allowed to affect the outcome. The experience of watching him feels intimate, because through the making of this film, a room is constructed where the young boy can take up space, acting temporarily outside of the walls of his own confinement.

As a starting point for this body of work, Källman set out to explore the spaces of the prison from an immediately physical vantage point. She entered the prison room with the notion of it being much like a camera, where light is only allowed inside in controlled portions. But what comes out of her visual engagement with these spaces is a much more complex set of questions that have to do with the human spirit in confinement. What grows out of the darkness experienced here, out of these tiny flickers of light reflected in mirrors and other shiny surfaces? What can these endless loops, signifiers of isolation and confinement, actually produce? To most of us the significance of prison spaces only exists at the very edge of our consciousness, too problematic to begin to grasp. What lies in the privilege of choosing where to be? What happens when a person’s scope of action is limited to the very narrowest of spaces, when their choices are minimized?

In these new works, Källman explores and visualizes the subjective experience of being confined. She gives visual and sonic shape to the prison cell and the person enclosed within it. The imagery carries a sense of surveillance characteristic of much of Källman’s work; a sense of being involuntarily or subconsciously watched. In confinement, basic choices become important. Using the simplest of means – light, reflection, sound, voice, rhythm, and space – Källman conveys a sense of humanity restricted, and a sense of a spirit bound up.

Given only the most minimal of spaces to act out one’s individuality, any significant sense of scope and potential will naturally be greatly diminished. In these works, the struggle to assert some kind of independence is expressed through the capturing of a persistent ability to maintain and re-create a space – even from within the condition of confinement. Through the use of sound, music, the moving and the still image, Källman constructs a stage for the tiniest gestures of individuality to unfold. In her deliberate representation of the smallest of actions and movements – actions that often only point back towards an isolated self – what seems to prevail is each individual’s inherent ability to re-define a space within his or her own vision. As such, these are images of hope and dignity. They quietly convey an intimate knowledge of our ability to make active use of space and of our own particular situation within it.

This, after all, may be the very core within us that makes confinement possible to endure.